I have recently had the privilege of participating in, and contributing to, three very different education conferences and I have just been invited to do the same at another – different again – at the turn of the year. The three were not just different from one another, they felt different in themselves. I am aware that the work I do, through the method I advocate, is boundary spanning and so is accessible and wholly relevant to pupils, parents/carers, local community members, teachers, school leaders, researchers… So, I am going to see this as a sign of things to come and that excites me greatly. A sort of reciprocal broadening of horizons. More of the same, please.

The first of the conferences was the Prince Albert Community Trust (@PA_CT) #illuminatingminds2018 Conference held in Sutton Coldfield Town Hall in October. Walking in, both the setting and the mood had something of a rock concert about it, music filled the place. Not 02 Arena styley. More, the vibrant, yet somehow more intimate buzz that I recall from watching The Jam at Newcastle City Hall in my college days. No one person put more into making the day work than the wonderful force of nature that is Kathryn Morgan , Director of CPD and Research Based Learning at PACT. Although, I am sure that Kathryn will be the first to tell you that you cannot pull off things like this on your own. I sat alongside fellow contributors Nina Jackson and Dr Tim O’Brien and marvelled as the collective body of each of the four Trust schools, brought together under this one roof, positively lifted that roof, with deafening cheers as images of their respective schools appeared alongside their school name on the big screen, centre stage. Note that I say ‘collective body’, for all school staff were present; premises staff, through to teachers. Governors, too. This tide of energy and enthusiasm marked the event and culminated in a rousing reception for PACT CEO Sajid Gulzar , and equally enthusiastic receiving of Sajid’s heartfelt exploration of WHY we do what we do, and HOW that might be carried out, with respect, kindness, dignity, empathy, equity, equality and social justice our watchwords; values at the forefront. By the way, you would be sorely mistaken to even begin to imagine this as something of a PACT “love in”. There was a very serious underlying intent; the laying out of a mission. Deputy CEO, Phillipa Downes , just as well received, shared her thinking on ‘Transparent Leadership’, and called for all PACT community members to sign up to that and share responsibility for chasing the very best outcomes, in the broadest terms, for the children attending all four schools. It was a memorable day, I learned so much.

The second of the conferences was organised by the formidable Emma Parker . Emma has done more than most to draw everyone’s attention to the #SENDcrisis. Some say that politics and education should be kept apart. My response to that is, How? They are inextricably linked. Although it would be good to kept certain politicians out of education. My view. The remarkable thing about the #SENDhelp Durham Conference, for me, was the mix of people in the room, on a Saturday. There were as many ‘parents/carers’ (as a category) in the room as any other group. Emma may have fulfilled many roles across the day, event organiser, ATL Executive member, teacher, to name but three, but, as she made crystal clear at the beginning of the day, Emma was present as the proud parent of a remarkable boy who had, that very week, accompanied her in delivering a 34,000 strong National Education Union SEND petition to the Department for Education in London. Just as there was a raw, and focused, energy in the room in Sutton Coldfield Town Hall (above), so there was at this conference, held at the impressive Durham County Cricket headquarters at Chester Le Street. The day closed with questions asked of a panel made up of Kieran Rose (The #ActuallyAutistic Autistic Advocate), Dr Mary Bousted (Joint General Secretary National Education Union), Nick Whitaker (HMI, Specialist Adviser, SEND), Emma Lewell-Buck MP, (Labour Member of Parliament for South Shields & Shadow Minister for Children and Families), Elaine Chandler (SENDIASS), and little old me. No ‘parent/carers’ on the panel, no, but many of the challenging, no nonsense questions were indeed asked by ‘parents/carers’ in the room, looking for answers to the significant challenges they faced.

A couple of things more from that particular day…

There was one gentleman, sat front and centre, attending my session, who seemed particularly engaged and interested. I shared my thinking and the work I do with schools across the UK on community capacity building, and we, as a group, discussed some of the key concepts. That included my questioning of the value of Ofsted Parent View, and surveys, on the whole. I think I used the word “nonsense”. In fact, I am sure I did. Rather, why not seek out stories and perspectives and work with them; a genuine attempt to work with parents/carers and school community. The gentleman came up to me afterwards and said he was very interested in the ideas we had explored, could he contact me in the near future and arrange for us to meet up and have a further conversation. His name? Nick Whitaker, HMI, Specialist Adviser, SEND. If you know me, you will understand my delight at this offer. The power of conversation, with everyone in the room.

And so, before we leave Chester Le Street and move on to Manchester… Kieran Rose, simply to say, a big thank you. What a role model, what an example. I attended Kieran’s session. He shared a bit about the fantastic work he does and then just threw the thing wide open, we all had a conversation about how things play out in our worlds, focused on the particular area of interest shared. Kieran had made the weather in the room, a range of perspectives were shared, respectfully received, and good healthy conversation flowed. Just as it should be. But how often is it?

The third of the conferences took place in Manchester this weekend gone, the ResearchSEND Conference at Manchester Metropolitan University, organised by Michelle Prosser Haywood and colleagues. The truly remarkable thing about this event was that across the day I had many conversations with fellow attendees who ranged from ‘parents/carers’ (I will apologise again for categorising people so. After all, I am a parent myself!) to SENCos, to professors of education, ending with a fascinating conversation with the delightful Britta Koerber, Director at Jessie’s Fund (‘Music can speak where words fail’). I did not know one from the other, who was who, until we reached a point where we said a little about ourselves. The interest was the same. A shared passion. The uniqueness of the event, for me, was capped by the fact that I was presenting with the brilliant Elly Chapple . Elly is the almighty force behind CanDoElla and #flipthenarrative Elly’s groundbreaking work and mission is inspired by her position as ‘parent/carer’ (mother) of the amazing Ella, but I would not and could not assume to categorise Elly, other than to say, she very much is an educator. We would all do well to listen to the story of Ella and Elly. Really listen, on every level, and learn at every turn. If you take nothing else from this blog, please accept this link as a valuable gift, here. I am thrilled and proud to be moving forward alongside Elly, planning and pursuing a truly exciting project. One that has inclusion and equality at its heart.

As said, I met and talked with many people on Saturday. I want to mention Gareth Morewood because he made me smile inside. He made me feel proud of the profession I belong to. Gareth spoke with intelligence, knowledge, experience and authority about just what it really means to carry the responsibility of being SENCo in your setting, and so very much more. Gareth shared insights and key messages with energy, passion and a sense of fun, all the while proudly referring to his equally enthusiastic colleagues present in the auditorium (on a Saturday) who “do the real work”.

Another illuminating input came from Jo Billington . Jo shared her work and research on working with families, highlighting how language is, alas, too often one of combat, adversarial. Further, that we (society) blame families for a child’s ‘bad behaviour’. As in Sutton Coldfield and Chester Le Street (above), those present offered varying perspectives on this, enriching the learning experience for all. Making that connection with Jo, sharing our work and research, and promising to continue to do so, was a highlight.

I would also like to mention Professor Michael Jopling and his citing of Hargreaves (1996) on ‘How teachers often justify practice’.

- Tradition (how it has always been done)

- Prejudice (how I like it done)

- Dogma (the ‘right way’ to do it)

- Ideology (the current orthodoxy)

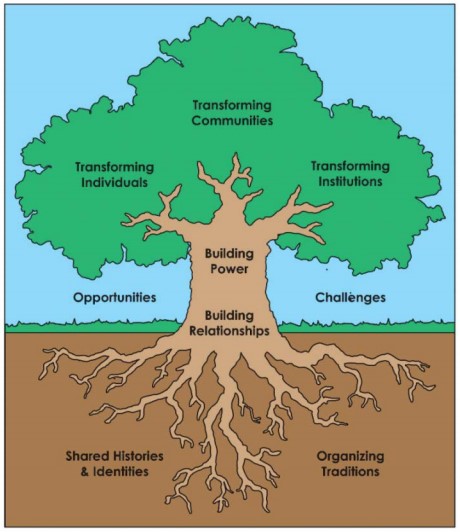

By the way, Professor Jopling was absolutely not being critical of teachers in sharing this. There was a point to it, and a point well made. I put it alongside everything else in the arsenal that fires up my believing in the mantra ‘better together’. Michael, building on his message, in a closing comment, stressed that we learning from and with one another is the thing.

At all three conferences I gave my input the subtitle, ‘John Smyth to John Smyth’. I will say why. It is relevant here. Just to say, that both John Smyths carry equal weighting in the way their words and actions have impacted my learning.

My first headship. Three days in. Having invited all parents/carers and community members in, I was stood at the front of a considerably large, seated group. I was thrilled by the turnout. I had introduced myself. I kept that short. “So, what do you want from me? Where are we going to take our school?” I boldly declared.

“What are you going to do about the school dinners?!”

The question came from a tall gentleman in the front row. The gentleman was Mr John Smyth, father of seven children in our school.

John, gesturing towards his son, alongside, explained that his son always came home hungry because he could not eat them. They were that bad.

Now, I am not sure why I responded in the way that I did but it was instinctive, I know that. I challenged John to come on in and find out for himself. In fact, I extended that offer to everyone present, and all those not. A school meal for all, on the house!

The following week, marked with promise of an Indian summer, they came, and they came. So, so much longer than the forty foot Megalosaurus Mr Dickens imagined waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Through the front door, into the hall where their children eagerly awaited them, out the side door into the adjoining courtyard, and back in by the fire door adjacent to the serving hatch. We had eighty odd take us up on the offer. We reckon over one hundred and twenty came on the day.

The crew in the kitchen had been in since 5:00 a.m. “Can we have roast beef and Yorkshire puddings?” I had asked Caroline, our redoubtable cook. “Oh, and jam roly-poly?” How self-indulgent can a man be?! Please excuse the irreverence but Jesus had nothing on these guys. The loaded plates just kept on coming.

Try as I did to suggest the adults might want to sit and wait rather than play at being a Megalosaurus, no way would they. We passed the word around that this must take as long as it takes and early afternoon lessons can slide. In something approaching a carnival atmosphere, children found parents and all were fed. Patience was needed and patience was exercised.

I spent a little time sat with father (John) and son. I told him that this was all his doing. His challenge had prompted this. I thanked him. He thanked me. We three tucked joyously into three good servings of Jam Roly Poly.

Before the end of that first half-term we called another open meeting. I introduced it by encouraging all those present (another big turn out) to think back to our first get-together, to consider any ‘promises’ I might have made and to evaluate our success or otherwise against those promises, and to challenge. “I ain’t going nowhere, I am here, listening.”

And so to John Smyth II… Professor John Smyth. A strand of my ongoing research has allowed me the opportunity to interview four world leading academics in the field of socially critical research. If I was to name the stand out thing that came from my conversation with Professor Smyth I would not hesitate. This is it, directly from the transcript of that interview:

One of the things I never presume is to know the existential reality of worlds I am investigating, indeed, I regard it is being presumptuous to even know what might be significant questions of the informants in these contexts.

What I am saying is that my ‘warrant to know’, comes from the lives of the informants I am working with, not from knowledge gleaned while sitting in my office or from the academy!

On reflection, I would say that John Smyth I’s question of me had triggered a sub-conscious way of being in me that viewed parents as informants, ones that I wanted to understand and get to know. Several years on, Professor John Smyth named it. John Smyth, the parent informant, afforded me a compliment I will treasure forever. On thanking me for all that I had done for his children (his words), he added, “You are not just a man in a suit are you, Mr Feasey.”

As the ResearchSEND Conference on Saturday drew to a close I was approached by a lady who is the founder of a Parent Forum in the North West. She asked me for my contact details and if I would be interested in joining them for a conversation on all that I had shared on Saturday, at an event she is organising. I will, I most certainly will.

Conferences come in all shapes and sizes. I wrote this blog because I wanted to share my experience. I wanted to applaud the efforts of those who organised the three concerts, for they all had a certain musicality about them (I am sure that Britta heard it too). Let’s hear it for the symphony of inclusivity and make sure that these events keep on happening and keep on being well supported. For all were as inclusive as they could be, befitting of conference aims and embracing of different perspectives. Indeed, I know the learning I took away from all three events was multiplied by the diverse range of interests and perspectives present in the room.

The fourth conference, at the turn of the year? I have been asked to present at a conference organised and hosted by Durham University, billed Teaching & Learning: The Reflective Practitioner. You can be sure that I will carry all my learning from the first three conferences forward in encouraging others to open their ears to all informants, prior to that reflection. And yes, I will use the words of Saul Alinsky again:

You organise with your ears, not your mouth.

And that includes organising yourself, marshalling your own thoughts. I learned so much from all of you in Sutton Coldfield, Chester Le Street and Manchester.

Thank you!