For children and adolescents, the most critical ecological transitions and intersecting connections are the interactions between home, school, and peer groups.

Soo Hong, 2011 p. 24

In earlier blogs I have explored the process-oriented field of community organising in seeking clearer strategies for how we can build meaningful relationships between families and schools. Typically, standard parent involvement approaches avoid issues of power and consign parents to support the status quo. In contrast, community organising approaches to school reform in the US, where there is a long-standing tradition of community organising, explicitly focus on power, intentionally building parent power. In my work with schools, I advocate the joining together of school narrative and community narrative, encouraging new points of connection through important conversations. Participants in these conversations learn that relationships can be stymied by a lack of understanding, distrust, or individual fears and anxieties. And so, by adopting and embedding a relationship-centred and dialogical problem-solving approach we root authentic home-school-community partnership in the realities of power, inequality, and a desire for social change.

Consider this…

In March 2017, the Māori tribe of Whanganui in the North Island of New Zealand celebrated the fact that the Whanganui river had been granted the same legal rights as a human being. The tribe has fought for the recognition of their river – the third-largest in New Zealand – as an ancestor for 140 years. Gerrard Albert, the lead negotiator for the Whanganui iwi [tribe] said all Māori tribes regarded themselves as part of the universe, at one with and equal to the mountains, the rivers and the seas. The new law, passed by the New Zealand Parliament in Wellington, now honoured and reflected their worldview.

Just one week later, a court in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand ordered that the Ganges and its main tributary, the Yamuna, be accorded the status of living human entities. The judges cited the example of the Whanganui river. The decision means that polluting or damaging the rivers will be legally equivalent to harming a person. The court sat in the Himalayan resort town of Nainital. I add the last sentence for no other reason than to mention my father was born there on 14 May, 1929 (Michael’s father served in the Army. My dad spent the first 18 years of his life in the foothills of the Himalayas!).

In the language of the Lakota cosmology, water is mni, an action of living. Emphasising commonality and connectedness rather than separation, instead of being something outside of ourselves that needs to be owned, protected and managed, mni is part of us and we part of it. Lakota rejection of the modernist understanding of water as a resource and insistence that it is a source of life resonates with the Whanganui iwi worldview, as stated by Albert:

We have fought to find an approximation in law so that all others can understand that from our perspective treating the river as a living entity is the correct way to approach it, as in indivisible whole, instead of the traditional model for the last 100 years of treating it from a perspective of ownership and management.

In the interests of harmony throughout this piece, let us adopt an ecological perspective…

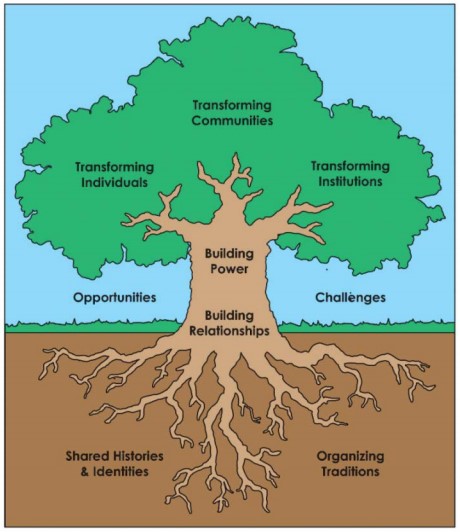

Warren and Mapp (2011) provide us with a tree metaphor in sharing their understanding of how strong forms of community organising work. They chose the metaphor of a tree because, they say, organising is a phenomenon that grows and develops. That organising efforts take time to mature, and they need to be intentionally cultivated and nurtured. Further, that strong organising efforts have deep roots.

Strong organising has deep roots in tradition. It draws on collective values and extant ties.

For as much as context very much matters, strong organising efforts share fundamental features. Warren and Mapp show these core processes building relationships and power – in the tree trunk. New relationships are built, and identities expanded. Relationships for long-term change, no silver bullet or top-down reform.

Organising efforts also respond to their environment, to the opportunities and constraints presented by changing political and educational contexts. Organisers must be sensitive to local experiences, needs, and knowledge.

By enacting these processes, organising groups work to transform communities, individuals, and institutions.

Warren and Mapp point out that groups that follow similar organising traditions will grow differently depending on local contexts; the context being the soil, shaped by local social and political history. This, they say, is because organising groups start where people are. They bring people together to share their concerns as well as their wants and dreams.

Soo Hong (2011) does indeed expressly call for an ecological view of parent engagement. In a core of three strands (2011), Soo Hong discusses the work of the developmental psychologist, Urie Bronfenbrenner, and his urging us to understand human development through an ecological orientation that considers the individual as embedded within multiple spheres of influence. He describes the environments within which individuals interact as nested structures.

It is the interconnectedness of individuals within and across sections that shapes an individual’s ability to learn, grow and develop. Soo Hong, rightly, in my view, highlights the fact that the home and school environments are hard to bring together. It is critical, she says, that we understand the interaction between environments.

For children and adolescents, the most critical ecological transitions and intersecting connections are the interactions between home, school, and peer groups.

Soo Hong, 2011 p. 24

I always enjoy reading the work of people who are bold enough to just say it. Enter stage left, Andrew Morrish:

The purpose of education is not to effect sudden transformations, but to foster gradual growth… To achieve this, a stand out leader has but one aim in mind: to create a culture that provides these conditions for growth so that the organisation can thrive, gradually and continually. No force-feeding or chemicals. No polytunnels or hothouses. Just good honest muck.

I guess that takes us back round to the idea of adopting an ecological view as we foster relationships, authentic partnerships, and drive community capacity building. An organic one, at that!

Finishing with a Whanganui proverb…

Ko au ko te awa. Ko te awa ko au.

I am the river and the river is me.

This Whanganui proverb describes the relationship between people and the environment, and in this context, the tangata whenua and their ancestral river. The mighty Whanganui river provided oranga (sustenance and wellbeing) to the people who resided on its banks. This was the source of their livelihood, their local ‘supermarket’, their ancestor. Without the river and all its bounty, life would become increasingly difficult. Without the river flowing freely, the land would soon become barren and unworkable. This whakataukī encourages people to be cautious in the way we treat Papatūānuku, the land, sea, and waterways. We are the kaitiaki (guardians) of this world. In our role as kaitiaki, people need to care for and respect our environment and our environment will care and provide for us.

The new status of the Whanganui river means if someone abused or harmed it the law now sees no differentiation between harming the tribe or harming the river because they are one and the same. Thinking on our school communities and the overlapping spheres of influence impacting on the lives of our young people, it may not be possible to match the wonderful achievements enacted in Wellington or Nainital, but we would do well to appoint ourselves as fiercely protective guardians of that particular ecosystem, nested or otherwise. Further, whichever metaphor we chose to represent the system in our school community context, might we take a leaf out of the Lakota cosmology and view community as they view mni. Emphasising commonality and connectedness rather than separation; an action of living.

I work with schools, in a coaching capacity, supporting them in community capacity building. More here

REFERENCES

Hong Soo (2011) a core of three strands: A New Approach to Parent Engagement in Schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Morrish, A. (2016) The Art of Standing Out: School Transformation, to Greatness and Beyond. London: John Catt: Woodbridge.

Warren, M. R. and Mapp, K. L. (2011) A Match on Dry Grass: Community Organising as a Catalyst for School Reform. Oxford: OUP.

Pingback: Community Soil and Lessons from Mycology: Mother Nature and the Wood Wide Web (Trees Can Count) – Community Capacity Building